99 results

Cash rules everything around me: in defence of housing markets

-

- Journal:

- Economics & Philosophy , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 19 March 2025, pp. 1-19

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Are Markets Amenable to Consequentialist Evaluation?

-

- Journal:

- Business Ethics Quarterly , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 December 2024, pp. 1-17

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- HTML

- Export citation

Change the Meaning, Save More Lives: Why Changing the Meaning of Commercial Compensated Collections of Substances of Human Origin Is Both Feasible and Preferable to Banning the Practice for Fear of Commodification

-

- Journal:

- Social Philosophy and Policy / Volume 41 / Issue 2 / Winter 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 06 February 2025, pp. 527-545

- Print publication:

- Winter 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

An Ontology of Social and Economic Reproduction: Modern Slavery, Housing, and Critical Realism

-

- Journal:

- Social Policy and Society , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 18 November 2024, pp. 1-12

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The Same Storm, but Different Boats: Unpicking the ‘Housing Crisis’

-

- Journal:

- Social Policy and Society , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 13 November 2024, pp. 1-11

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Seed commodification and contestation in US farmer seed systems

-

- Journal:

- Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems / Volume 39 / 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 31 October 2024, e26

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

The moral limits of what, exactly?

-

- Journal:

- Economics & Philosophy , First View

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 12 September 2024, pp. 1-23

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

Crude Knowledge: Petro-Periodicals and Resource Sovereignty

-

- Journal:

- International Journal of Middle East Studies / Volume 56 / Issue 3 / August 2024

- Published online by Cambridge University Press:

- 23 January 2025, pp. 446-464

- Print publication:

- August 2024

-

- Article

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

1 - Introduction

-

- Book:

- Politicising Commodification

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 1-10

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

13 - The Policy Orientation of the EU’s Post-Covid NEG Regime and Its Discontents

- from Part IV - Comparative Analysis and Post-Pandemic Developments

-

- Book:

- Politicising Commodification

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 323-352

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

7 - EU Governance of Public Services and Its Discontents

- from Part II - EU Economic Governance in Two Policy Areas

-

- Book:

- Politicising Commodification

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 132-164

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

8 - EU Governance of Transport Services and Its Discontents

- from Part III - EU Economic Governance in Three Sectors

-

- Book:

- Politicising Commodification

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 167-203

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

6 - EU Governance of Employment Relations and Its Discontents

- from Part II - EU Economic Governance in Two Policy Areas

-

- Book:

- Politicising Commodification

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 95-131

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

11 - Labour Politics and the EU’s NEG Prescriptions across Areas and Sectors

- from Part IV - Comparative Analysis and Post-Pandemic Developments

-

- Book:

- Politicising Commodification

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 269-306

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

14 - Conclusion

- from Part IV - Comparative Analysis and Post-Pandemic Developments

-

- Book:

- Politicising Commodification

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 353-358

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

4 - How to Assess the Policy Orientation of the EU’s NEG Prescriptions?

- from Part I - Analytical Framework

-

- Book:

- Politicising Commodification

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 53-72

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

9 - EU Governance of Water Services and Its Discontents

- from Part III - EU Economic Governance in Three Sectors

-

- Book:

- Politicising Commodification

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 204-230

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

10 - EU Governance of Healthcare and Its Discontents

- from Part III - EU Economic Governance in Three Sectors

-

- Book:

- Politicising Commodification

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024, pp 231-266

-

- Chapter

-

- You have access

- Open access

- HTML

- Export citation

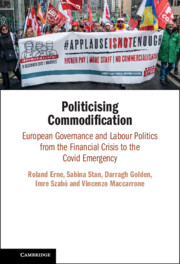

Politicising Commodification

- European Governance and Labour Politics from the Financial Crisis to the Covid Emergency

-

- Published online:

- 30 May 2024

- Print publication:

- 06 June 2024

-

- Book

-

- You have access

- Open access

- Export citation

2 - The Politics of Class

- from Part I - Histories of the Present

-

-

- Book:

- The Cambridge Companion to Contemporary African American Literature

- Published online:

- 14 December 2023

- Print publication:

- 21 December 2023, pp 46-62

-

- Chapter

- Export citation